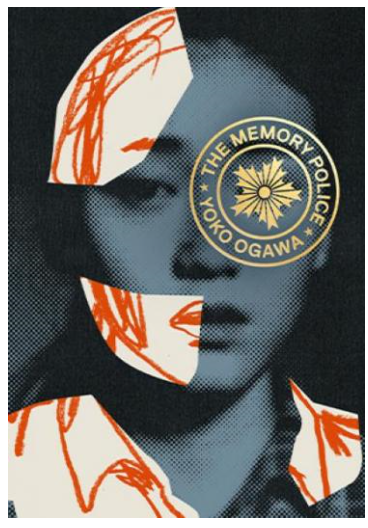

I didn’t hear mention of the Yōko Ogawa’s 1994 novel The Memory Police until 2016, when people referenced it with regards to how fascist governments change people’s reality by slowly altering the parameters of normal life until only the reality of the oppressor remained. At the time, in the wake of Donald Trump’s election, I’d already read It Can’t Happen Here and then Night of Camp David, not to mention that Michael Wolff book and so I didn’t pursue this.

What a mistake!

The Memory Police is actually tonic for the purely political novel. As with Franz Kafka, its political dimensions only serve to accent the greater absurdities of human existence and mortality.

This dreamlike book tells the story of life on an island governed by a group called “The Memory Police,” who seemingly at random remove items from people’s lives. The losses have varying significance. Sometimes it’s calendars or music boxes, other times roses or books and ultimately body parts. When an item is removed, the people forget it ever existed. A few, however, remember. The Memory Police hunts down those who can remember, to enforce a strict elimination of objects or ideas deemed irrelevant.

The premise. naturally evokes the kind of gaslighting practiced by totalitarian governments around the world and throughout history. But I think there’s much more to it, especially when the people start to lose memory of their bodies.

One thing I considered, perhaps more horrifying and merciless even than a dictatorship would be a diseases or conditions that rob people’s cognition. Or diseases like diabetes or certain cancers that cost people body parts. Ultimately, The Memory Police seems to be about mortality, the little things that life takes from us along the way and our struggles to preserve what’s precious.

Certainly, it’s a fascinating book and something far bigger than a political commentary (though, it’s that, too.)