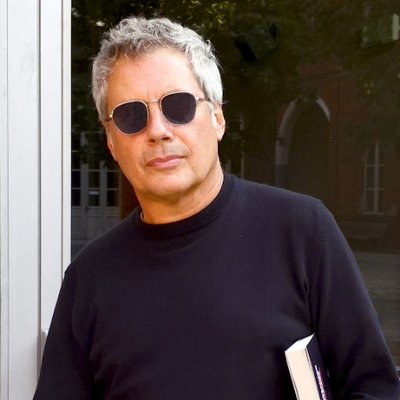

There’s no shortage of takes about how Internet culture is ruining real world culture. I’m sure I’ve written my share. The Game: A Digital Turning Point by Alessandro Baricco (translated from Italian by Clarisssa Botsford) takes a strong opposing view and it convinces. I can never go back to my skeptical and lazy quick takes, having read this argument by an Italian novelist, sreenwriter, playwright, essayist and creative writing instructor. Everything about Baricco would lead you to assume he’d harshly critique online culture and yet, he sees salvation in it.

It’s nostalgia for the twentieth century, not online culture, he argues, that is truly dangerous for humanity. He makes this argument as gently as he can:

“I hope people who feel nostalgic don’t get me wrong. The twentieth century was many things, but over and above everything else, it was one of the most horrific hundred years in the history of humankind, perhaps the most horrific. What made it unspeakably devastating was the fact that it wasn’t the result of a failure of civilization or even an expression of brutality: it was the algebraic result of a refined, mature, and wealthy civilization.”

To hammer the point home, he recaps:

“A country that had been the cradle of our ideas of freedom and democracy constructed a weapon so lethal that, for the first time in their history, human beings possessed something they could use to destroy themselves. Finding themselves in a position to use it, they did so without hesitation. Meanwhile, on the other side of the Iron Curtain, the evil fruits of revolutions, by means of which the twentieth century had dared to dream of better worlds, led to immense suffering, unprecedented acts of violence, and terrifying dictatorships. Is it clear now why the twentieth century is not only the century of Proust but also our nightmare?”

Baricco traces the digital revolution from its origins in the video game Spacewar! (play it here) through the development of the first web pages, online commerce, social mediaand the epoch of big data and artficial intelligence we’re entering now. He structures his book as a topography of this new world — a sister to physical reality where some old elites have been replaced by new elites and some old elites have seen their power distributed among the masses.

Admittedly, some of this argument rhymes with the tech triumphalism of the 1990s, when we some believed the internet would be a great democratizing force. If Wal-Mart was culture’s bogeyman then, Amazon, Google, Facebook and Apple are now.

Baricco is no Utopian. He describes a new world, better by comparison to the blood-soaked one it replaced, though not perfect by any means, or even fair. The digital world is, as Baricco describes, a game with myriad, complex and changing rules. Games have winners and losers. Well-made games do not have obvious and surefire strategies for success. It’s like the stock market — if a strategy existed for producing steady gains with no losses, everybody would utilize it. Well-meaning, well-qualified and hard working people can lose this game, just as they frequently lost all of the games we played before.

A trap for the nostalgic is to insist that pre-digital experiences like seeing a play or symphony in person or reading a physical book or visiting a museum are somehow more real than their digital counterparts. “Listening to the Vienna Philharmonic live at the Musikverein is not the same as watching it online, but for most of humanity it is a choice between nothing and something really quite exciting. It’s not hard to choose,” he writes.

Those of us, and I include myself in this, who feel dislocated from their pre-digital dreams and ambitions would do well to remember that, though it may be harder to publish a book or to produce a play these days, “In its way, the Game showed far greater promise: it opened up all the gates and widened access to theaters, museums, and bookstores. A significant number of new faces started to circulate in places where they had never been seen before.”

Baricco stresses the benefits of open-mindedness and to recognize the futility of stubbornly insisting on old ways of doing things — there is no bulwark against what’s happened, what’s happening or what’s to come. Society will not consent to going back and for good reason. To survive, practitioners of arts and humanities will have to succeed in a game where skills can only be learned by playing.

Interestingly, he recommends that education, which has been sloweest to adapt, needs to change the most. This change, which had been resisted as Baricco wrote, has been forced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our son, 10 years old, grew up digital. As Baricco recalls his own child trying to interact with a photograph in a newspaper as if it were a touchscreen, we remember our son, around 3 years old, try to swipe the television to another channel and showing visible disgust at a screen so stupid as to ignore a users touch. He has been remote learning entirely since the Pandemic broke in March 2020 and while this arrangement isn’t for everybody, he has thrived.

Of course, he wants to go back to a physical classroom but as I’ve watched him succeed at computer-enabled scholarship, I realize that we can’t, and shouldn’t ever go back to education as it was. Remote learning is a skill and our son’s practice of it means that he can now access the best teachers in any discipline, no matter where he lives and where they do, if they have an online practice. Why settle for the best guitar teacher in town if the best in the country or world is available?

Further, as I watch friends and family in their 40s and 50s earn professional certificates and degrees online, I think that what our remote students are going through now might pay off massively later in life. In March, Google will launch its first low cost, online professional certifications. For a lot of adults, online learning isn’t natural. I dipped my toe in only recently, because of a professor friend posted a lecture series about Kafka’s The Trial to Udemy. I suspect that many seeking the Google certifications will feel some anxiety about it. Today’s remote learners won’t. For them, an online course will have no more or less value than a book does to me when I read it between covers or on the Kindle app.

The Game is a fascinating study, has a refreshing take and I highly recommend it. I can’t do it justice here but hope I caught its flavor.